React Hooks - How to Transistion your App from React Components to Hooks

React hooks are a new feature added in the 16.8 release of the React JavaScript library. Hooks were intended to make it easy to use state and other reusable functionality in functional components. Before hooks, reusable functionality relied on class-based components and often required the user to use higher-order components (HOCs) and render props. While HOCs and render props are great on their own, they quickly become awkward when you try to use each of them multiple times in a single component.

Why Care About React Hooks?

If class components are working well for you, then you might wonder if learning about hooks is worth your time. I believe they’re worth it for several reasons.

First, the React community is quick to adopt new practices and abandon old ones. The React team has heavily promoted hooks as the path toward writing React code that is clearer and easier to understand. Dan Abramov, a popular member of the React dev team, is a very strong proponent of hooks. And where the React dev team leads, the React community usually follows.

This tendency to follow trends isn’t unique to the React community, and it doesn’t mean that class components are going away. They currently make up the bulk of most large React applications, and I expect that to remain true for the foreseeable future. But over time, I expect that many interesting libraries and utilities will only work with hooks. Hook-based libraries can make it very easy to work with forms, animations, and external data sources like web sockets. The catch is that you can’t use hooks in class-based components.

Library authors are going to have to make a choice, and it appears that hooks will be what they choose as long as the React dev team is promoting hooks as the preferred path forward. As a developer, hooks also offer you the opportunity to write more concise code that is easier to debug and understand; they’re not just a pointless trend that offers no benefit.

You definitely shouldn’t abandon class components if you love using them. They’re still great, and they’re still a big improvement over using React.createClass back in the React dark ages of 2013. But if you’re working on React apps as a member of a large team or make use of many external libraries, you’re going to encounter hooks in the wild sooner or later.

What React Hooks Do

Hooks offer a way to extract stateful logic from a component to make that logic easy to test and reuse. As a result, hooks can be used as an elegant replacement for sometimes-hacky workarounds like nested higher order components, providers, and render props. None of these features alone are bad, but as we touched on earlier, having to use all of them together in a single component can be a source of accidental complexity.

Hooks can also be used to split complex components into smaller files and keep related bits of functionality together. For example, in a class component that needs to subscribe to a WebSocket, some of the code will have to go in the componentWillMount lifecycle method, and some will have to go in the componentWillUnmount method. Using a hook, we could keep all of the WebSocket code together in a single hook function instead of splitting it across multiple lifecycle methods. In fact, this is exactly the example we’re going to examine in the next section.

Converting a Class Component to a Hook Component

Now that we’ve discussed what hooks are and why you’d want to use them, let’s dive into the details of how to convert a class component to a hook component.

Note that you shouldn’t feel the need to convert your class components to use hooks without a good reason. We’ll be walking through the conversion process because starting with something you already know will make hooks easier to understand, and at the end of the exercise you’ll end up with two identically functioning components that will help you easily compare and contrast the two approaches.

As an example, we’re going to look at a React app that uses a class for a fairly common use case: making a WebSocket connection when the component mounts and closing the WebSocket connection when the component unmounts. The component is used as part of a simulated chat app.

You can find the example in a StackBlitz workspace here. The class component we’re interested in is in the WSClass.js file. Let’s take a look at its code:

import React from 'react';

import NavBar from './containers/NavBar';

import ChatWindow from './containers/ChatWindow';

import ChatEntry from './containers/ChatEntry';

export default class WsClass extends React.Component {

constructor() {

this.state = {

messages: ["Test message"],

newMessageText: ""

}

}

componentDidMount() {

this.socket = new WebSocket("wss://echo.websocket.org");

this.socket.onmessage = (message) => {

const newMessage = `Message from WebSocket: ${message.data}`

this.setState({

messages: this.state.messages.concat([newMessage])

})

}

}

componentWillUnmount() {

this.socket.close();

}

onMessageChange = (e) => {

this.setState({ newMessageText: e.target.value });

}

onMessageSubmit = () => {

this.socket.send(this.state.newMessageText);

this.setState({ newMessageText: "" });

}

render() {

return (

<>

<NavBar title={"WebSocket Class Component"} />

<ChatWindow messages={this.state.messages} />

<ChatEntry text={this.state.newMessageText}

onChange={this.onMessageChange}

onSubmit={this.onMessageSubmit}/>

</>

);

}

}

As you can see, this is the kind of component you’ll encounter in a typical React app. In the constructor, we set up the component’s initial state.

In componentDidMount, we establish a WebSocket connection to wss://echo.websocket.org. As its name implies, this is a socket that echoes back whatever we send to it, which is perfect for our example app.

In componentWillUnmount, we call the close method on the WebSocket because we won’t be using it anymore. Closing the connection when we’re finished with it is important because in a real application with a chat window, there’s a good chance we’d be opening and closing the chat. If we don’t close the connection when our component unmounts, it’ll remain connected until the user reloads the page or navigates away to a different page. Over time, our app would use more and more memory until it crashes the user’s browser!

We also add an event handler to handle the WebSocket’s onmessage event. This handler will be triggered whenever we receive a message from the socket. Our handler function will receive a MessageEvent as its only parameter. The event object’s data property contains the text of the message. Inside the event handler, we use this.SetState to add the data to our app state’s messages array.

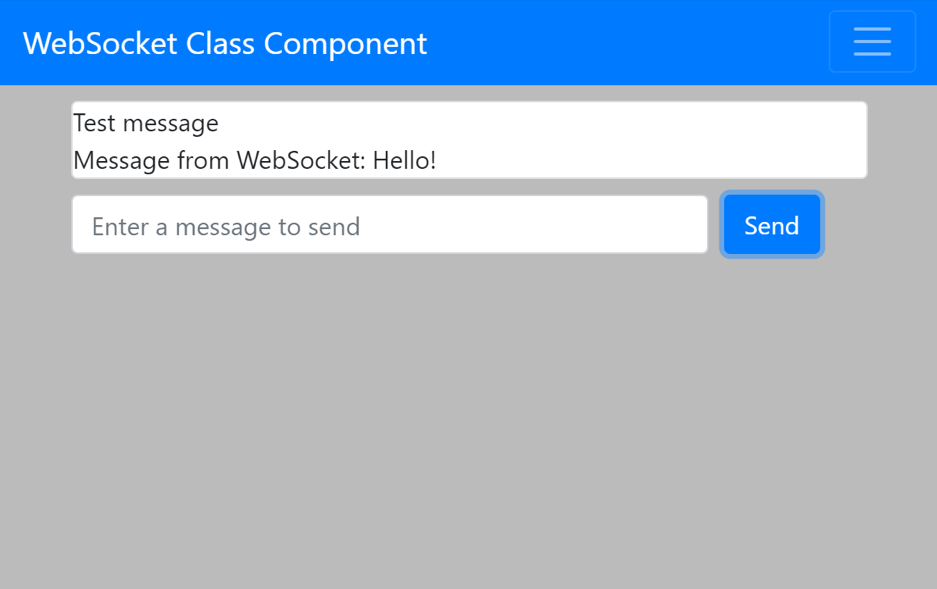

Next, in the render method, we lay out the components of our chat application. ChatWindow displays our chat messages, and ChatEntry lets us send chat messages. If you enter a message and click the send button, you’ll see that the WebSocket server echoes it right back:

Now that we’ve seen how this app works as a class component, how would we go about creating it as a function component using hooks? If you’d like to jump ahead and it in action, you can find the final result on StackBlitz in the WSHook.js file. Otherwise, keep reading as we walk through the code.

Here’s what our simulated hooks-based chat component looks like:

import React, {useState, useEffect, useRef } from 'react';

import NavBar from './containers/NavBar';

import ChatWindow from './containers/ChatWindow';

import ChatEntry from './containers/ChatEntry';

export default () => {

const [newMessage, setNewMessage] = useState("");

const [messages, setMessages] = useState(["Test message"]);

const [state, setState] = useState({

messages: ["Test message"],

newMessageText: ""

});

const socket = useRef(new WebSocket("wss://echo.websocket.org"))

useEffect(() => {

socket.current.onmessage = (msg) => {

const incomingMessage = `Message from WebSocket: ${msg.data}`;

setMessages(messages.concat([incomingMessage]));

}

});

useEffect(() => () => socket.current.close(), [socket])

const onMessageChange = (e) => {;

setNewMessage(e.target.value);

}

const onMessageSubmit = () => {

socket.current.send(newMessage);

setNewMessage("")

}

return (

<>

<NavBar title={"WebSocket Hook Component"} />

<ChatWindow messages={messages} />

<ChatEntry text={newMessage}

onChange={onMessageChange}

onSubmit={onMessageSubmit}/>

</>

);

}

You’ll notice that it looks pretty similar to the class-based component. So similar that you might wonder if it was worth the work to convert it. And in reality, the answer is that in many cases, your class components are perfectly fine as-is, and converting them to use hooks is a waste of time.

Additionally, you’ll find that in some cases, hooks make your components more difficult to reason about and understand. We’ll address those issues as we walk through the code to ensure you can make an informed decision about when and where you’ll want to use hooks.

We start our component with two uses of the useState hook: one to store the new message that we’ll be sending over the WebSocket, and one that stores the array of messages that we’ll be displaying in our chat window. This isn’t too different from the way we used state in the class component — we just have our new message string and messages array in separate state variables instead of in a single state object.

Next, we call the useRef hook to set up our WebSocket. useRef is a handy helper that lets us set up a reference to a JavaScript object that persists between component renders. In a functional React component, the entire function is called every time the component re-renders in response to a state change. Usually this is fine, but sometimes we really need things to stick around – like our WebSocket. Without useRef, our WebSocket would be re-created every time we type a letter into the text box, and soon we’d have hundreds of open WebSocket connections.

Next, we have two calls to the useEffect hook. useEffect is the hook you’ll want to use to replace the functionality of the class component lifecycle methods componentDidMount and componentWillUnmount. When you call useEffect, you pass it a function that contains code that should run when the component mounts and returns a function that will be run when the component unmounts.

Here’s a brief example to illustrate the concept:

useEffect(() => {

console.log(“Component is rendering”);

return () => { console.log(“Component is being destroyed.”); }

})

That’s not too bad: just basic JavaScript, where a function returning a function is common. There’s one catch with useEffect, though: by default, it’ll run every time the component re-renders. However, useEffect can take an array of dependencies as its second argument. When you specify a list of dependencies, the effect will only run if one of those dependencies has changed.

This is why we have two useEffect calls: we want to re-bind the WebSocket’s onmessage handler on every render because our handler creates a closure around the messages variable, so failing to re-bind will cause our handler to use stale data, and our chat app won’t work properly.

We don’t want to close the WebSocket on every re-render, though, so we put the close handler in its own effect with socket in the array of dependencies we pass as the second argument to the useEffect call. This ensures that the socket will only be closed when the component is destroyed, which is what we want.

Using effect hooks in this way can be confusing to reason about, especially if you’ve been working with class components for years. Sometimes, having named lifecycle methods will just be a better fit for the problem you’re trying to solve. Hooks are great for many use cases, but class components aren’t going to disappear. You should keep using them when you feel they’re the right fit for the problem you’re solving and use functional components and hooks where they’ll make your code easier to understand.

After we’ve set up our hooks, the rest of the component is largely the same as the class component. Instead of creating instance methods to handle updates, we’ve assigned functions to variables that we can pass into the components that render our chat room.

Overall, the functional component with hooks is slightly more concise than the class component, at the expense of being slightly harder to reason about if you’re accustomed to using class components.

One big advantage of hooks is that it would be relatively easy to extract the WebSocket functionality out into a custom hook that could easily be reused in other components. To do the same thing with a class component, we’d have to create a higher order component which would take more work to create and would be more awkward to use.

Conclusion

And we’re done! We’ve successfully walked through the process of converting a stateful class component to a stateful hook component.

As we’ve seen, hooks aren’t magic. They don’t do anything that class components couldn’t do. They do help you write code that’s more concise and easier to understand in some situations. It’s entirely possible to keep basing your apps on class components and only create hook components when you need to interact with hooks-only libraries.

On the other hand, if you love hooks and want to use them everywhere, don’t hold back! Given the level of enthusiasm for hooks from the React dev team and the wider React community, hooks aren’t likely to disappear any time soon.